Posted Dec. 3, 2008

Word is getting around about the city’s new camping ordinance guidelines as reported in the latest Street Roots. Reporter Amanda Waldroupe sheds light on new procedures that slipped under the radar as the city touted shelters, warming centers and assorted good-n-fuzzies. But the truth is, the city is expanding its opportunities to roust and displace, without notice, the growing number of our neighbors trying to stay warm, dry and safe at night. This, even as the city says shelter providers report about a 50 percent increase in the numbers of families seeking shelter.

Loaded Orygun adds great commentary to the subject. Read it here, and lend your voice to the discussion.

Read “New guidelines waive 24-hour notices to homeless campers” after the jump

Posted by Joanne Zuhl

New guidelines waive 24-hour notices to homeless campers

Portland Police change the rules to allow immediate sweeps of camps on public and private property

By Amanda Waldroupe

Contributing Writer

Toby Dempster has been revolving between jail and homelessness since 1986. He’s proud of himself for being able to stay off heroin and meth since 2002, and he’s looking forward to getting back to work as a carpenter.

He still does some carpentry — using some scrap, he built himself a small, wooden trailer that he painted green and hooked up to the back of his bike. The trailer’s filled with his belongings, including a white propane heater, a knife, bedding and clothes.

“It goes with me every day,” he says.

Dempster didn’t build the trailer for work, but out of the necessity to protect his belongings from the police when they conduct camp sweeps and tell homeless individuals to move on.

“They come and jerk you up and take everything you own,” Dempster says bitterly. “It’s not right.”

Dempster, who has been homeless for the past two years, says he’s lost count of how many times he’s been swept from a camp. He guesses six or seven times, and says it’s always around one or two in the morning.

Every time, the police have taken away Dempster’s possessions, including his heater. It takes a month, he says, of collecting cans and scrap metal to recoup the losses.

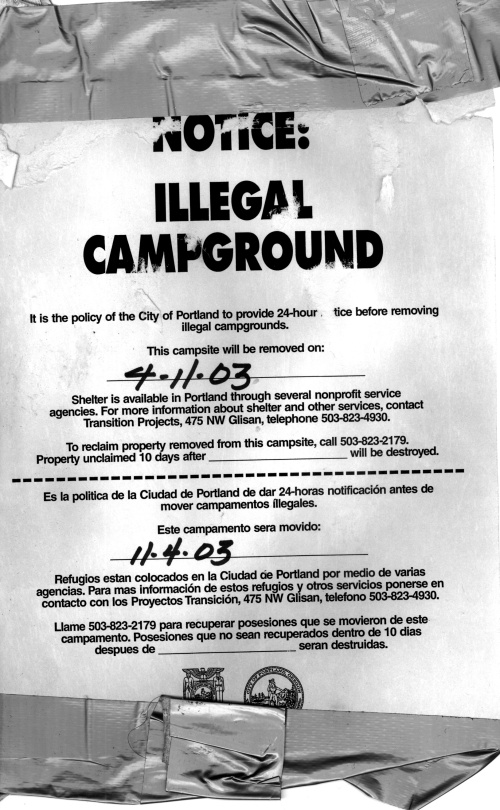

The police, according to Dempster, have never given him or the camps he’s stayed in the

24-hour notice police are required to give before the sweep takes place.

Dempster’s experiences, shared by many other homeless individuals who camp in Portland, may only get worse with a new standard operating procedure, or guidelines, for how the Portland police enforce the city’s controversial anti-camping ordinance.

The new guidelines say homeless and civil rights advocates, have created definition loopholes and exceptions to the 24-hour posting requirement, making it permissible for police to not give notice before a sweep.

The old guidelines mandated that exceptions to providing 24-hour notice were made for camps on private or state property, and in cases where illegal activities and emergencies occurred.

The new guidelines continue to provide those exceptions, but now add city and parks property to the list. They also interpret permanent postings and signs prohibiting camping as providing sufficient notice before a sweep.

“Neither of these changes mean that the police can’t post in these situations, only that they don’t have to,” says Marc Jolin, executive director of the outreach agency JOIN.

The changes broaden the number of situations in which the police are exempt from giving 24-hour notice to the point that it leaves virtually no situation where the police are required to provide 24-hour notice to a camp before it is swept.

“I don’t think the police have the authority to do that under state law,” says David Fidanque, the executive director of the ACLU of Oregon.

Fidanque is referring to ORS 203.079, the state law requiring that 24-hour notice be given to camps not on “public property that is a day-use recreational area” or a “designated campground.” The law also says removal of camps needs to be done in a “humane and just manner.”

Advocates for people experiencing homelessness share Fidanque’s concern, saying that homeless people camped in many areas are no longer protected by state law.

“If you look at the (state) law as a whole, it’s clear that municipalities are supposed to have a humane policy toward homeless people camping on public property,” says Monica Goracke, a lawyer with the Oregon Law Center.

Goracke says that in order for campers to be treated humanely while swept, the police need to give 24-hour notice to all camps, regardless of their status and location, and contact social services before the sweep.

“The new operating procedure opens the door to non-humane enforcement that penalizes people because they have nowhere to live,” Goracke says.

Sgt. Matt Engen, who patrols Old Town/Chinatown and was in charge of re-writing the guidelines, maintains that the new guidelines are both legal and humane.

“If an officer was going to act inhumanely, I really don’t think a few words on a piece of paper would change that,” Engen says.

When pressed to provide an example of a place where homeless individuals could legally camp and be given 24-hour notice, Engen offered no specifics.

“If you are on public property that’s not a street, a sidewalk, a right of way closed to the public, or a park, you get 24 hours worth of notice,” Engen says.

However, the city’s sidewalk obstructions ordinance makes it illegal to sit or lie on a sidewalk or street during designated times. The anti-camping ordinance explicitly makes it illegal to camp in parks.

Engen also admits that the police are more lenient if a homeless individual is in a “non-impact” area.

“There are pieces of public land that are utilized by the public far more heavily than others,” Engen says. “We encourage folks to find areas to camp that are low-impact.”

The guidlines also now provide a new definition of an “established campsite” as “locations where a camp structure such as a hut, lean-to or tent is set up for the purpose of maintaining to live in and exists on public property, other than a sidewalk or roadway.”

“It appears to me that they made a big effort to exempt what we think of as the very temporary campsites,” Goracke says.

What Goracke is referring to are camps more temporary or “non-established” in nature, where someone will put up a tent for the night, take it down in the morning, and move on.

“I think the difference does exist in practice,” Jolin says, adding that it is difficult to discern when a camp becomes established.

Those sorts of camps are now exempt from the 24-hour notice as well. But with a 50 percent to 60 percent increase reported by providers and the city in homeless families and individuals seeking shelter (see “City concedes need for more shelter,” Street Roots, Nov. 14, 2008), the necessity for homeless individuals to camp may only increase.

“I think (the police) think this is an effective way to discourage camping,” Goracke says.

Goracke may be onto something: if the police do not give 24-hour notice to non-established camps and are successful in eradicating them from Portland, camps that could be considered established will never have a chance to form. The new operating procedures may spell out the means to end camping in Portland.

“I wouldn’t make it a secret that’s a benefit (of the new operating procedures),” Engen says.

According to Engen, Police Chief Rosie Sizer’s office directed the police in late spring to review and update the guidelines. That is coincidentally about the same time that as many as 100 homeless individuals and advocates protested the anti-camping ordinance and police sweeps of camps in front of City Hall.

The consensus among officers he consulted, Engen says, was that “(the SOP) is not particularly broken.” When re-writing it, Engen aimed for a holistic policy outlining how to “post and clean up campsites,” providing the police with more discretion and freedom when confronted with a camp situation, and opportunities to work more closely with social services.

“I didn’t want it to be a policy on how we enforce illegal camping laws,” Engen says.

Engen says that by collaborating with JOIN, a special 800 number was created for police to leave messages that quickly route to the appropriate outreach worker’s cell phone. Jolin says it already has proven useful.

“The heads-up gives us the ability to make sure that the clean-up doesn’t set back (a person’s) process of getting off the streets,” Jolin says.

The effect that camp sweeps have on homeless individuals can be a negative blow. Dempster says that being told by the police to move his camp, and having his possessions taken away makes him depressed and more prone to get back on drugs.

“It devastates us,” Dempster says. “They got us hating life.”

“It just keeps us rotating, moving,” says another homeless man, who identified himself as King. “And you’re back to the shopping cart.”

“I think the police as a tool for social change can be a blunt tool,” Engen says. “It’s a position we neither seek nor envy.”

“They don’t care,” Dempster says.

Jolin says that the tension between police officers and homeless people, as well as the emotional and economic difficulties homeless people face as a result of the camp sweeps make giving 24-hour notice all the more important.

“We hear from campers all the time that what matters most is how and when the cleanups are done,” Jolin says. “Whether they get notice is an important part of that.

“Giving specific notice whenever possible is good for everyone involved.”

The constitutionality of Portland’s anti-camping ordinance already is under question. Goracke sent a demand letter to the city attorney in November 2007, stating concerns that the ordinance cruelly and unusually punishes homeless individuals because of their status as homeless.

“I don’t think the ordinance as it is currently applied is humane in letter or in spirit,” Goracke says.

Goracke is currently working with the city attorney’s office to reach a settlement. She says if the case makes it to court, she would tack on the new guidelines to the case.

“If the city and police wake someone for camping or having a structure in a public place, and they do that without giving 24-hour notice, they’re going to be inviting a challenge in court,” Fidanque

Posted by Joanne Zuhl

Pingback: Lawyers for homeless to sue city over camping ordinance « For those who can’t afford free speech

We stumbled over here by a different web page and thought I might as well check things out.

I like what I see so i am just following

you. Look forward to looking at your web page repeatedly.

Amy